Upon deboarding the plane in Leticia, Colombia, I was greeted by an empty airport and a heavy blanket of humidity that made me want to remove all of my clothing on the spot. Leticia’s status as a city comes into question when compared to a metropolis like Medellin, but when you consider the rest of the settlements in the Amazon, it shines like a beacon in a vast ocean of jungle, butted up against the legendary Amazon River and the Brazilian border town of Tabatinga. Across the river and a quick boat ride away is Peru, or rather, the small village of Santa Rosa de Yavari, located on an island in the middle of the second-largest river in the world.

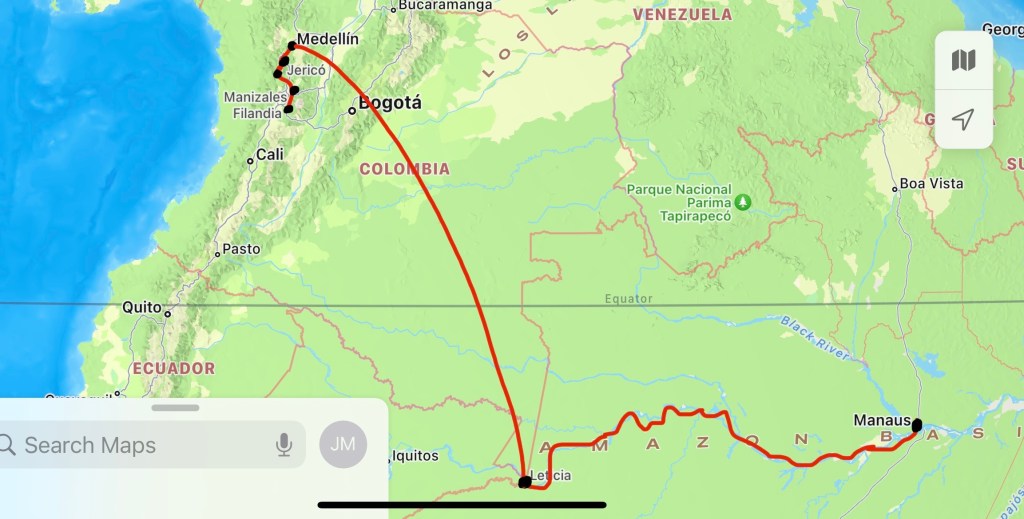

I arrived in Leticia with the intended goal of getting a taste of what the Amazon had to offer, before I planned to continue my journey along the Amazon River towards the Brazilian city of Manaus, by way of a multi-day boat ride on a hammock ship.

Admittedly, I didn’t think much at first of the local cuisine that I would be eating, mostly for lack of knowledge, but that would quickly change.

After taking a tuk-tuk to my local accommodation, I realized that I would be sleeping in a 12-person dorm, thick with humidity, its rotating fans good for nothing but recirculating the hot jungle air around the room. Trying to look for a food and and a place to cool down, I wandered into downtown Leticia.

Imagine my surprise when I was confronted with menus in local eateries that had words that I had never considered as food before — Copoazú, Pirarucu, Milpesos, Beiju, Cajú.

My time in the Amazon quickly turned into an unexpected lesson in a unique local cuisine, which I can bet is found nowhere else in the world.

Meals here are made up of completely different staples than in the United States. The Amazonians have a taste for fried sticks of yucca also known as cassava. They are dense and mildly flavored, similar to a boiled potato. They go well with something called salsa rosa— a cold cocktail sauce made of mayo and ketchup mixed together. Another staple is a toasted and ground cassava flour called Fariña, which acts as a sort of savory and crunchy topping that can be sprinkled on top of any meal. And then there was the Beiju, a prepared food that is also made of cassava flour, also known as tapioca, that can be made into flat crepe-like shapes. The beiju is a crepe-like dish — stuffed with cheese, meat, or vegetables to become an incredibly delicious and chewy alternative to bread. I ate 3 of these in one serving, changing the filling each time.

During one of my walks through the small village of Puerto Nariño, I came across a woman selling homemade ice cream out of her house. The menu of flavors was packed with a list of dozens of flavors that came across as indecipherable — Copoazú, Milpeso, camu camu, graviola, acerola, jabuticaba. All of the flavors came from local fruits, many of which are not found outside of the tropical climate of the Amazon.

I settled with trying the Copoazú ice cream, (pronounced Coh-poh-ah-zoo) which would quickly become my favorite flavor of the bunch. The fruit itself is a large, round and brown fruit that looks similar to a sweet potato on the exterior, with a creamy yellow flesh that has a strong flavor reminiscent of a mix of pineapple, banana, and jackfruit.

It also became customary to order a new fruit juice every time I stopped at a local restaurant. Acerola’s red pulp and skin made a great sour juice, similar to that of cherries. Graviola, known in English as soursop, is a creamier and sweeter alternative to Acerola’s sour flavor. Cajú, or Cashew fruit is one of my personal favorites. The fruit that hosts the cashew nut that we eat, actually tastes sour, sweet and slightly astringent, somewhat like a persimmon. It makes a great juice too.

As for the local meat, apart from chicken and the occasional piece of beef, fish was the protein of choice for the locals. I became familiar with the local delicacy, Pirarucu. It is a giant air-breathing fish that is filleted into boneless steaks and cooked as an incredibly versatile white meat that’s somewhere in between a cod and halibut.

I finally tried it on one of my last nights in Puerto Nariño, while I was recovering from a fever in the only hotel that had air conditioned rooms in the village. The owner cooked dinner every night for the guests, serving the food family style alongside good conversation. It was on this night that he served a nice filet of breaded, pan-fried Pirarucu with plantains and yucca and a pitcher of Copoazú juice to wash it all down.

It was a simple but delicious meal. A great way to round out my fairly uneventful visit to the small Amazonian town.

Now, whenever I arrive at a new destination, It has become a ritual of mine to first make sure that I am checked into my accommodation, followed by immediate search for a good place to eat.

But I truly believe that the habit has a good reasoning behind it.

I’ve since recognized the importance of the cultural medium that food offers when attempting to experience a new physical space. It may be more than just an ice cream flavor, and it might just tell a story of the history and identity of the local inhabitants that some might believe can only be properly be experienced through other mediums, such as language or cultural events.

It’s an opportunity to learn about the place you are visiting without having to struggle through translator apps and social cues. After all, we all can appreciate good food for what it is.

My unexpected schooling in Amazonian gastronomy remains a highlight of my short stint in the jungle, and I aim to go back with the sole purpose of getting my hands on a Copoazú once more.

Leave a comment