By Joel Marcus Morales II

BEIRUT

In central Beirut, not far from the half-destroyed remnants of the port, lies The Colony — a rundown hostel where one can find the most seasoned and unusual backpackers on the planet.

In mid-October of 2025, I arrived at The Colony with my Dutch friend Sophie. We had both decided to take a spontaneous flight from Istanbul, Turkey, just a few days prior. Between the two of us, we must have 3-4 years’ worth of backpacking experience, some of which we spent together traveling Central and South America in 2023, where we initially met.

By sheer coincidence, our paths crossed in Istanbul, and our desire to step into a new adventure together led us to Beirut.

The man in charge of the day-to-day operations of The Colony was a 30-something-year-old Lebanese guy named Rami, who volunteered as the manager and worked without proper financial compensation. The only thing he received in return for running the hostel was free accommodation, which wasn’t always guaranteed because overbooking was a common issue. The terrace ended up being his makeshift bed most nights. Often, he dragged you into his manic conversations that you couldn’t escape from.

Water and electricity at the hostel were constantly cut off for hours or days at a time. Sophie and I quickly learned to shower whenever we had the chance. The Colony was in a dilapidated state, with beds, fans, and general facilities needing some serious attention, while the owners were supposedly living off the profits somewhere in Canada.

Even for a couple of seasoned backpackers that didn’t mind getting a little dirty, The Colony left us desperate for basic amenities, including hot water and proper air circulation.

But what it lacked in amenities, it made up for in the people it attracted.

A general rule of hostel culture is: the more remote and unpopular the destination, the better the people. While places like Berlin and Rio might attract people looking for a quick weekend of fun, The Colony attracted the chainsmoking, skinny, long-haired types. They had the best stories to tell and made the best company if you were open to having a conversation with them.

It was through such conversations that I quickly came to find out that many of the people passing through the hostel were either going to or coming from Syria. Most of them traveled solo, some in groups, but there was a consensus among them that Syria was a unique destination, still untouched by mainstream commercial tourism. It sounded like a true hidden gem for backpackers — something that can rarely be found in today’s influencer-saturated world.

Even more shocking was that a year ago, in October 2024, none of this would have been possible to consider. Last year, it seemed as if the Syrian Civil War was doomed to remain a frozen conflict. The fighting had mostly stopped, the government had consolidated its position, and the media had long since moved on to other hot spots in the geopolitical landscape. Yet in a mere 11 days in November and December of 2024, a fringe rebel group went from starting a small offensive in the north to capturing Aleppo, the second largest city in the country, before continuing south and capturing Damascus, effectively ending the 13-year civil war and 54 years of dictatorship under the infamous al-Assad dynasty.

Now, after hearing first-hand testimony from other backpackers, I felt as if my mind was already made up before I even realized it.

I had to go to Syria to see it for myself.

I decided to go alone, without Sophie, for the last week of my trip. She had her mind made up to take her time traveling in Lebanon without rushing through, and I had a strict, non-negotiable return flight to Texas in a week. I only had time to visit one, maybe two cities max.

To prepare for the next leg of my journey, I withdrew a few hundred US dollars from the local ATM in Beirut. I had heard from other backpackers that withdrawing cash in Syria in any amount was not possible, due to the sanctions that had locked out Syria from the global banking system for the past decade. Bank cards would definitely be out of the question. I decided that $400 was enough to cover all the basics of accommodation, transportation, and food for a week in the country. Phone data was not going to be a concern this trip, as it was not worth the hassle of getting a local Syrian to help me buy a SIM card. I would rely solely on spotty wifi and pre-downloaded maps to guide me through the country.

With money out of the way, the visa was the only remaining issue. Luckily for me, entering Syria through a land border allowed me the ability to get a visa on arrival, albeit for a price. US citizens had to pay the most out of all the nationalities upon entry — $200. EU citizens had to pay $75, and some nationalities inexplicably paid nothing. These prices only recently came into effect after the chaos of the revolution settled down in the months following December ‘24.

I got up early on October 26th to try to cross the border and arrive in Damascus as soon as possible. I began my day with a two-hour bus to the border, followed by a stop at customs to get stamped in, and another taxi into Damascus. The entire route between Beirut and Damascus took a total of 4-5 hours. I was in the capital by early afternoon that same day.

I arrived with no hotel reservation, as it’s impossible to book online in advance. But as I disembarked my taxi, I felt completely detached from all concern. I was in a new country, in a place I never thought I would have a chance to visit. People have survived worse, I reminded myself.

DAMASCUS

After being dropped off on the edge of the old city, near the 2000-year-old city walls, I began walking with my 40-liter bag on my back and my smaller daypack slung over my shoulder. I started on foot through the old, charming streets of the Bab Touma neighborhood, lined with artisan shops that sold copper wear and handcrafted wooden goods.

At first glance, the neighborhood reminded me of a street in the Roma area of Mexico City. The sidewalks were noticeably clean, as were the buildings. They were brick with white stucco and looked as if they had just been renovated. As I walked, I couldn’t help but notice a group of women walking down the street opposite me, wearing nicely decorated head scarves, draped lightly over their hair, and wearing fashionable high-heeled shoes. I saw middle-aged men working their artisan shops, and young boys gathered in groups, talking loudly amongst themselves.

Everywhere I looked, I noticed a common feature: the new national flag of Syria, now depicted as three horizontal stripes colored green, white, and black, with three red stars evenly spaced in the white stripe. The flag was everywhere — above shops, stuck on the inside of windows, painted in alleys as graffiti, and as decals on cars. Every sign of the previous regime, including the old red-white-black flag, had been erased so thoroughly that I couldn’t spot a single statue or portrait of what was once a totalitarian regime with a cult of personality that rivaled North Korea in omnipresence.

I continued my aimless walk until I unintentionally stumbled upon the Old Souq of Damascus — an ancient covered marketplace that is a common feature of most Middle Eastern cities. I was completely overwhelmed by the sight of my discovery.

I squeezed through the throngs of people, stepping to the side to avoid taxis that drove through the crowded market street while avoiding boys on bicycles. I noticed men pushing supplies on carts, and women doing their daily shopping. Funnily enough, no one even looked my direction. I was invisible in the best way possible, and I reveled in it.

There I was — a sweaty backpacker with my bags weighing on me, with a big smile growing on my face. I was steeped in this great feeling I can best describe as a “traveler’s high”. Something that I rarely get when backpacking nowadays, but sometimes present whenever I arrive in a new country, or find myself self-aware of some strange situation I’ve gotten myself into.

As I made my way through the Souq, I appreciated the fact that I was walking through a place that was inaccessible to most foreigners only a few months ago. I was looking straight into the daily lives of Syrians who had been largely untouched by foreign visitors since before the war began.

The crowded market street gave way to a more low-key working-class neighborhood of the Old City, where streets were filled with heavy car exhaust, and sidewalks were full of people walking single-file, sharing the space with vendors displaying their goods on unrolled mats on the ground.

Just as I began to notice the weight of my bags on my sore shoulders, I entered the first hotel I saw. With the help of Google Translate, I made it clear that I wanted to see a room. The man at the reception looked pleased to see a foreigner, and eagerly showed me the windowless closet that had been repurposed for solo travelers like myself. For 7 dollars a night, I can’t say I wasn’t tempted, but I knew I should treat myself to something nicer to celebrate my first day in Syria.

Just across the street was another hotel, where I found a room with double beds, a nice view, and my own bathroom for $20 a night. I chose this as my home for the next 2 nights in Damascus.

A small piece of advice: choose your hotels wisely in Damascus. Bedbugs in my cheap hotel room had done a number on my skin, and by the time I caught a bus to Aleppo, I was covered in clusters of small, incredibly itchy bites on my neck and torso.

As I went to pay the hotel owner, I passed him one of my $20 bills. He took it, examined it closely, and looked up at me with a disapproving nod. It was too wrinkled. In fact, there was a small tear in the top center of the bill where it had been folded multiple times. In Syria, like in most of the developing world, cash is king, but if the cash is US dollars, it needs to be in pristine condition — no exceptions.

After some begging, he finally relented and took the money. I quickly checked my makeshift bank at the back of my hardcover journal, where all of my currency was stuffed in the last page. It turned out that half of my bills were invalid, all with some form of tear or line where they had been folded countless times. I was now having to travel for a week with only half of the money I had brought with me.

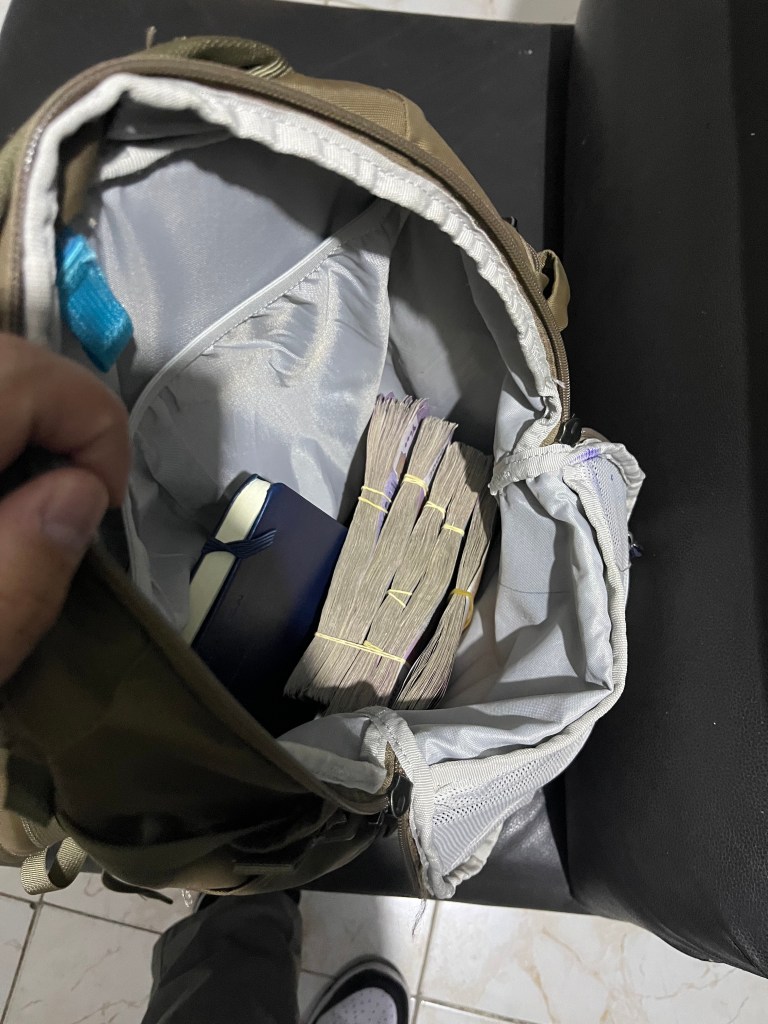

I took the rest of my usable bills and changed them for local Syrian pounds at a currency exchange. The workers at the exchange gave me the smallest denomination of Syrian bills, which left me with stacks upon stacks of thick, purple currency that was wrapped tightly with rubber bands and which took up most of the space in my backpack. Interestingly enough, the notes still had Al-Assad’s face on them. When I decided to pay for the second night at the hotel with Syrian pounds, the hotel receptionist made sure to ritualistically spit on the image of the former dictator when I handed him a fresh stack of currency to count.

But I really couldn’t ask to be in a better place with only 200 dollars in my pocket.

I found it to be the cheapest country I’ve traveled to by far. The average meal would cost anywhere from 60 cents to $2. An average stay at a hotel was $20 a night, but I could find a cheaper room if necessary. The buses between cities ranged in price from $5 to $8 — Incredibly affordable for bus rides that lasted hours and covered hundreds of miles. Taxis tended to be slightly more expensive, but still reasonable compared to prices in neighboring Lebanon.

Setting aside my reluctance to generalize a whole country, I can say with confidence that Syrians are some of the nicest people I have ever met. Of course, suave slick-talking — especially that of taxi drivers — can be misconstrued as kindness. I try not to be naive enough to ignore that. At the end of the day, most people just want foreign business and currency, which I absolutely cannot blame them for. Yet time and time again, I encountered the same basic interaction:

I would begin by saying asalsam aleikum, the traditional Arabic greeting, followed by my attempt to ask for something I needed, either with the help of Google Translate or simply by pointing frantically at the item I wanted. When they’d realize I wasn’t from Syria, my ethnic ambiguity was set aside, and they asked where I was from.

I would usually say I was from Mexico for two reasons: To avoid having to explain that I was born in the United States, but my family is from Mexico, thus explaining my brown skin. Often, when I began by saying I was from America, they would look at me, confused, and repeat their question because I looked more similar in complexion to them than what they imagined an American to look like.

In one particular instance, a boy shook my hand when he realized I was a foreigner visiting his shop, and without letting go, he kept shaking it as he pulled me to the back of the store to introduce me to his father. The only words I could make out were “Baba — Almaksik!” “Dad — Mexico!”

Overall, Damascus was a rewarding place to visit, and I highly recommend it to people who are interested in getting their feet wet exploring the Middle East. My only regret is not having a local friend to show me around to the best spots to sit and smoke hookah — though that, of course, is a result of my unfortunate level of spoken Arabic.

After 2 full days in the capital, I was ready to move on. I had visited most of the Old City, the impressive Umayyad Mosque, the Old Souq, and the National Archeology Museum. I found myself unknowingly walking in big circles in the Old City and running into the same side streets and alleys I had already come across countless times. In the end, I was satisfied with my experience thus far in Damascus, but my time was limited, and I had the urge to see as much as possible before I was forced to head back to Beirut to catch my return flight.

It took me around 2 minutes from the moment I stepped out of my taxi at the bus station to board a bus. I didn’t bother to ask around for the prices of other companies. I just wanted to go north. There was nothing particularly noteworthy about the buses; they looked like any other I had taken during my travels through Latin America. The only difference was the passengers.

Across the aisle from me, seated directly to my right, was a bearded man, maybe my age. The only article of clothing that remotely marked him as some man of authority was a pair of cheap camouflage pants. I had seen others like him walking the streets of Damascus. They always had AK-47’s slung over their shoulders, but didn’t appear to have any responsibilities beyond patrolling the streets and talking with people. I’m still unclear about who they were or what they actually did.

The man played games on his phone at full volume, while his rifle’s strap was secured over the back of the seat in front of him. The gun bounced as the bus drove down the dusty highway — the barrel of the AK-47 was haphazardly aimed at the head of a man who sat in the seat in front of me. I sat there nervously, hoping the rifle wasn’t loaded and didn’t have a sensitive trigger.

ALEPPO

Whereas Lebanon was mountainous and green, Syria was desert. The view from my window passed impressive mountains on the road leading out of Damascus. The rugged landscape eventually gave way to flat desert as we moved north. Every settlement and every building along the road to Aleppo exhibited the scars of war.

Most buildings were pockmarked with bullet holes, while many were twisted skeletons of concrete pillars and collapsed floors. Rusted metal rebar peeked through the cracked concrete of unsalvagable wreckage.

The destruction was so immense, I wondered if attempting to rebuild a country like this was even feasible. This was the first time I had seen so much destruction up-close.

By the time I arrived in Aleppo five hours later, it was mid-afternoon. Most of the passengers who began the journey with me in Damascus had long gone by the time we arrived at the bus terminal. As we stretched our legs and grabbed our luggage, we were immediately swarmed by taxi drivers looking to make some money. I chose the least annoying one and let him take me to a hotel that I had heard about from an Italian backpacker at The Colony.

The taxi ride took me directly through the destroyed suburbs of the city; it impressed upon me further the reality of the situation Aleppo was in. 10 years ago, this city was the Stalingrad of the Syrian Civil War. From 2012 to 2016, Aleppo was at the frontline of a struggle between Rebels, the Syrian Government, ISIS, and occasional Russian air strikes, with civilians bearing the brunt of the consequences.

I remember being a teenager, watching videos of the house-to-house fighting on Vice News. It seemed so far away back then.

I felt a distinct, poignant tinge of homesickness as I entered the city.

I stayed at Hotel Al-Andalus, the most beautiful accommodation I had the opportunity to visit during my month-long trip. Built in the latter part of the 1800’s during the French colonial era, it was miraculously spared from the war, though the receptionist later showed me a cracked tile in the lobby, where a missile had flown through the window, crashed into the ground, and failed to explode.

My first meal in the city was a big spread of char-grilled beef and vegetables, with a side of assorted bean dips to fill my belly. The waiter kindly offered me a cigarette and a cup of gritty black coffee.

I spent the rest of my afternoon aimlessly wandering the streets, snapping photos of anything I came across.

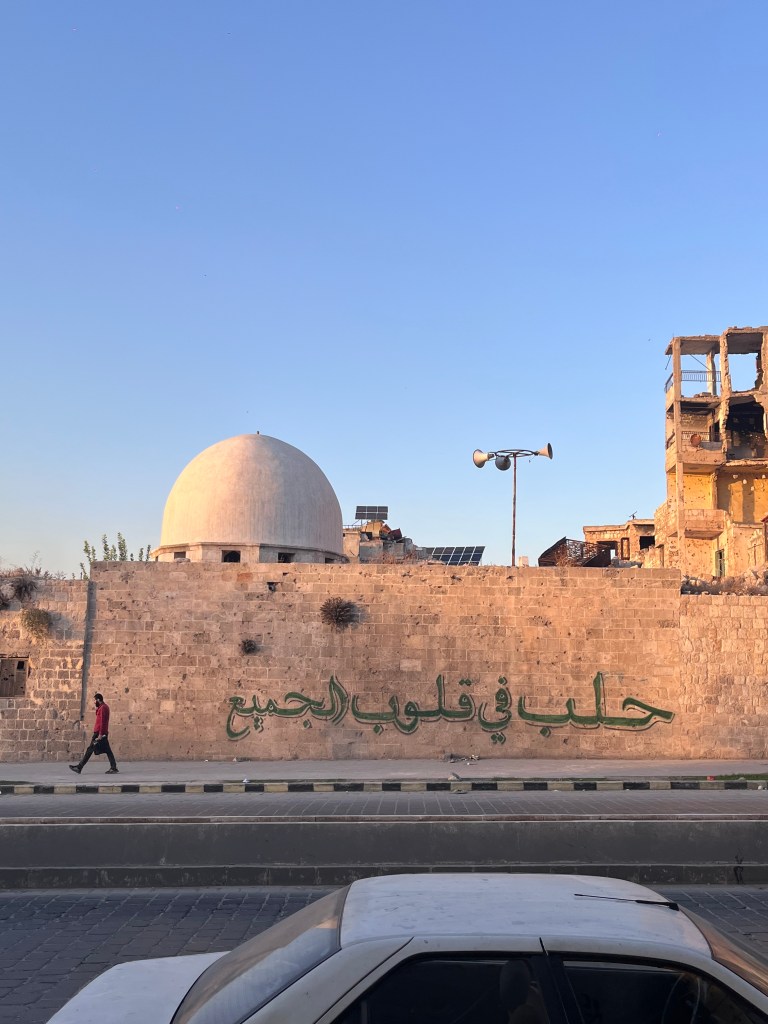

Aleppo has only a few things in common with Damascus. They are both choked with car exhaust, everyone smokes cigarettes, and there is a general lack of local restaurants in the city center. However, Aleppo impressed me in so many more ways than Damascus did. I loved the Aleppo Citadel, a beautiful ancient fortified castle atop an unbelievably steep hill in the center of the city. The Souq, although half-destroyed, was even more charming than the one in Damascus, and the people were even more kind and welcoming in Aleppo than they were in Damascus, if that was even possible. It felt more down-to-earth.

All of the humdrum of daily life persisted despite rows of bombed-out buildings. The citizens of Aleppo are slowly rebuilding their city. It was incredible to see large, multi-story buildings with all their upper floors abandoned—dusty concrete pillars holding up empty levels—while the ground floor, or sometimes a single room on a floor, was lit at night and inhabited by a shop or a resident.

During my regular evening downtime, when I would lounge in the hotel lobby and charge my phone, one of the hotel workers would sit down next to me and play the Oud — a pear-shaped string instrument similar to a lute. I’d watch him riff and improvise all these beautiful songs, with words he would sing off the cuff. I wish I could have understood what he was saying. He made good company.

One evening, as I sat in front of the Citadel, I was approached by a young Syrian girl wearing a red vest. I replied with my usual Asif, Inglezi—sorry, English. She laughed, handed me a small piece of paper, and continued on her way. The paper was in Arabic, and I couldn’t read it; the only things I could make out were a few heart-shaped drawings.

Not far from where I was sitting, I noticed more young people in red vests approaching passersby, and a small gathering of locals near the Citadel’s main gate, where the red vests mingled with the crowd. It turned out to be a community blood drive. Nearby, men sold coffee, children played, and young mothers sat with strollers at their sides.

In front of the Citadel, it could have been anywhere in the world. It even reminded me of my hometown. It’s not hard to see that everyone, everywhere, strives for the same things — happiness and the chance to grow up in peace.

The next afternoon, I was taken by a local man named Joud. I met him during my walk around the labyrinth that is the Aleppo Souq. He showed me the view from atop the castle, took me to get falafel in the market, and showed me his father’s copper-wear business. We spent hours together, practicing his English. When I asked what his future looked like, he explained his desire to stay in Syria, have a family, and help rebuild his country.

Aleppo made me feel invested, and more importantly, it made me feel hopeful for the future of Syria and its people. From afar, this place can seem disconnected from reality; just a news headline that you can turn a page on. But I found that these people looked just like me, and expressed themselves in a way that I could relate to. They had a great sense of humor that never made you feel like an outsider or as if you were intruding upon a closed community. Anyone could be a Syrian.

I made my way back to Lebanon early the next day and arrived at The Colony exhausted, with the first signs of a runny nose. I had to fight with all of my taxi drivers to get back to Beirut, with one driver even kicking me out of his taxi out of frustration with our inability to agree on a fair price.

But as I settled into my plastic chair on the outdoor terrace of the hostel, each of the interesting characters I had met during my previous week in Lebanon, including my friend Sophie, made their way onto the terrace to join me. Over a few bottles of wine and some cigarettes, everyone was eager to exchange stories. We laughed and talked until the early morning, as one by one, people said goodbye, and made promises to see each other again when the time came.

Leave a comment